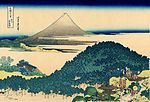

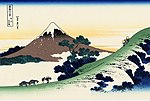

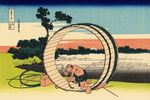

36 Views of Mount Fuji (富嶽三十六景 Fugaku Sanjūrokkei) is an ukiyo-e series of 46 large, color woodblock prints by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849). The series depicts Mount Fuji in differing seasons and weather conditions from a variety of different places and distances. It actually consists of 46 prints created between 1826 and 1833. The first 36 were included in the original publication and, due to their popularity, 10 more were added after the original publication.

While Hokusai's 36 Views of Mount Fuji is the most famous Ukiyo-e series to focus on Mount Fuji, there are several other series with the same subject, including 36 Views of Mount Fuji, by Hiroshige, and 100 View of Mount Fuji, also by Hokusai. Mount Fuji is a popular subject for Japanese art due to its cultural and religious significance. This belief can be traced to the The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, where a goddess deposits the elixir of life on the peak. As Henry Smith explains, "Thus from an early time, Mt. Fuji was seen as the source of the secret of immortality, a tradition that was at the heart of Hokusai's own obsession with the mountain."[2]

The most famous single image from the series is widely known in English as The Great Wave off Kanagawa (神奈川沖浪裏 Kanagawa-oki nami-ura), although a more correct translation might be, "Off Kanagawa, the back (or underside) of a wave." It depicts three boats being threatened by a large wave while Mount Fuji rises in the background. While generally assumed to be a tsunami, the wave was probably intended to simply be a large ocean wave.

Each of the images was made through a process whereby an image drawn on paper was used to guide the cutting of a wood block. This block was then covered with ink and applied to paper to create the image. The complexity of Hokusai's images includes the wide range of colors he used, which required the use of a series of blocks for each of the colors used in the images.

| № | Image | Name | Japanese | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | The Great Wave off Kanagawa | 神奈川沖浪裏 | Kanagawa-oki nami-ura |

| 2 |  | Mount Fuji in Clear Weather (also known as Red Fuji) | 凱風快晴 | Gaifū kaisei |

| 3 |  | A Shower Below The Summit | 山下白雨 | Sanka hakū |

| 4 |  | Fuji seen through the Mannen bridge at Fukagawa, Edo | 深川万年橋下 | Fukagawa Mannen-bashi shita |

| 5 |  | The Fuji seen from the Surugadai hill, Edo | 東都駿台 | Tōto sundai |

| 6 |  | The coast of seven leagues in Kamakura | 青山円座松 | Aoyama enza-no-matsu |

| 7 |  | Senju in the Musashi Province | 武州千住 | Bushū Senju |

| 8 |  | Tama River in the Musashi Province | 武州玉川 | Bushū Tamagawa |

| 9 |  | Inume pass in the Kai Province | 甲州犬目峠 | Kōshū inume-tōge |

| 10 |  | Fujimi Fuji view field in the Owari Province | 尾州不二見原 | Bishū Fujimigahara |

| 11 |  | Asakusa Honganji temple in the Eastern capital (Edo) | 東都浅草本願寺 | Tōto Asakusa honganji |

| 12 |  | Tsukada Island in the Musashi Province | 武陽佃島 | Buyō Tsukuda-jima |

| 13 |  | Shichiri beach in Sagami Province | 相州七里浜 | Soshū Shichiri-ga-hama |

| 14 |  | Umegawa in Sagami Province | 相州梅沢庄 | Soshū umezawanoshō |

| 15 |  | Kajikazawa in Kai Province | 甲州石班沢 | Kōshū Kajikazawa |

| 16 |  | Mishima pass in Kai Province | 甲州三嶌越 | Kōshū Mishima-goe |

| 17 |  | Lake Suwa in the Shinano Province | 信州諏訪湖 | Shinshū Suwa-ko |

| 18 |  | Ejiri in the Suruga Province | 駿州江尻 | Sunshū Ejiri |

| 19 |  | The Fuji from the mountains of Tōtōmi | 遠江山中 | Tōtōmi sanchū |

| 20 |  | Ushibori in the Hitachi Province | 常州牛掘 | Jōshū Ushibori |

| 21 |  | A sketch of the Mitsui shop in Suruga street in Edo | 江都駿河町三井見世略図 | Kōto Suruga-cho Mitsui Miseryakuzu |

| 22 |  | Sunset across the Ryōgoku bridge from the bank of the Sumida River at Onmayagashi | 御厩川岸より両国橋夕陽見 | Ommayagashi yori ryōgoku-bashi yūhi mi |

| 23 |  | Sazai hall - 500 Rakanji temple | 五百らかん寺さざゐどう | Gohyaku-rakanji Sazaidō |

| 24 |  | Tea house at Koishikawa. The morning after a snowfall | 礫川雪の旦 | Koishikawa yuki no ashita |

| 25 |  | Shimomeguro | 下目黒 | Shimo-Meguro |

| 26 |  | Watermill at Onden | 隠田の水車 | Onden no suisha |

| 27 |  | Enoshima in the Sagami Province | 相州江の島 | Soshū Enoshima |

| 28 |  | Shore of Tago Bay, Ejiri at Tōkaidō | 東海道江尻田子の浦略図 | Tōkaidō Ejiri tago-no-ura |

| 29 |  | Yoshida at Tōkaidō | 東海道吉田 | Tōkaidō Yoshida |

| 30 |  | The Kazusa Province sea route | 上総の海路 | Kazusa no kairo |

| 31 |  | Nihonbashi bridge in Edo | 江戸日本橋 | Edo Nihon-bashi |

| 32 |  | Village of Sekiya at Sumida River | 隅田川関屋の里 | Sumidagawa Sekiya no sato |

| 33 |  | Bay of Noboto | 登戸浦 | Noboto-ura |

| 34 |  | The lake of Hakone in the Sagami Province | 相州箱根湖水 | Sōshū Hakone kosui |

| 35 |  | The Fuji reflects in Lake Kawaguchi, seen from the Misaka pass in the Kai Province | 甲州三坂水面 | Kōshū Misaka suimen |

| 36 |  | Hodogaya on the Tōkaidō | 東海道保ケ谷 | Tōkaidō Hodogaya |

| 37 |  | Honjo Tatekawa, the timberyard at Honjo | 本所立川 | Honjo Tatekawa |

| 38 |  | Pleasure District at Senju | 従千住花街眺望の不二 | Senju Hana-machi Yori Chōbō no Fuji |

| 39 |  | Goten-yama-hill, Shinagawa on the Tōkaidō | 東海道品川御殿山の不二 | Tōkaidō Shinagawa Goten'yama no Fuji |

| 40 |  | Nakahara in the Sagami Province | 相州仲原 | Sōshū Nakahara |

| 41 |  | Dawn at Isawa in the Kai Province | 甲州伊沢暁 | Kōshū Isawa no Akatsuki |

| 42 |  | The back of the Fuji from the Minobu river | 身延川裏不二 | Minobu-gawa ura Fuji |

| 43 |  | Ono Shinden in the Suruga Province | 駿州大野新田 | Sunshū Ōno-shinden |

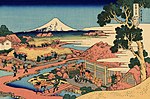

| 44 |  | The Tea plantation of Katakura in the Suruga Province | 駿州片倉茶園の不二 | Sunshū Katakura chaen no Fuji |

| 45 |  | The Fuji from Kanaya on the Tōkaidō | 東海道金谷の不二 | Tōkaidō Kanaya no Fuji |

| 46 |  | Climbing on Fuji | 諸人登山 | Shojin tozan |